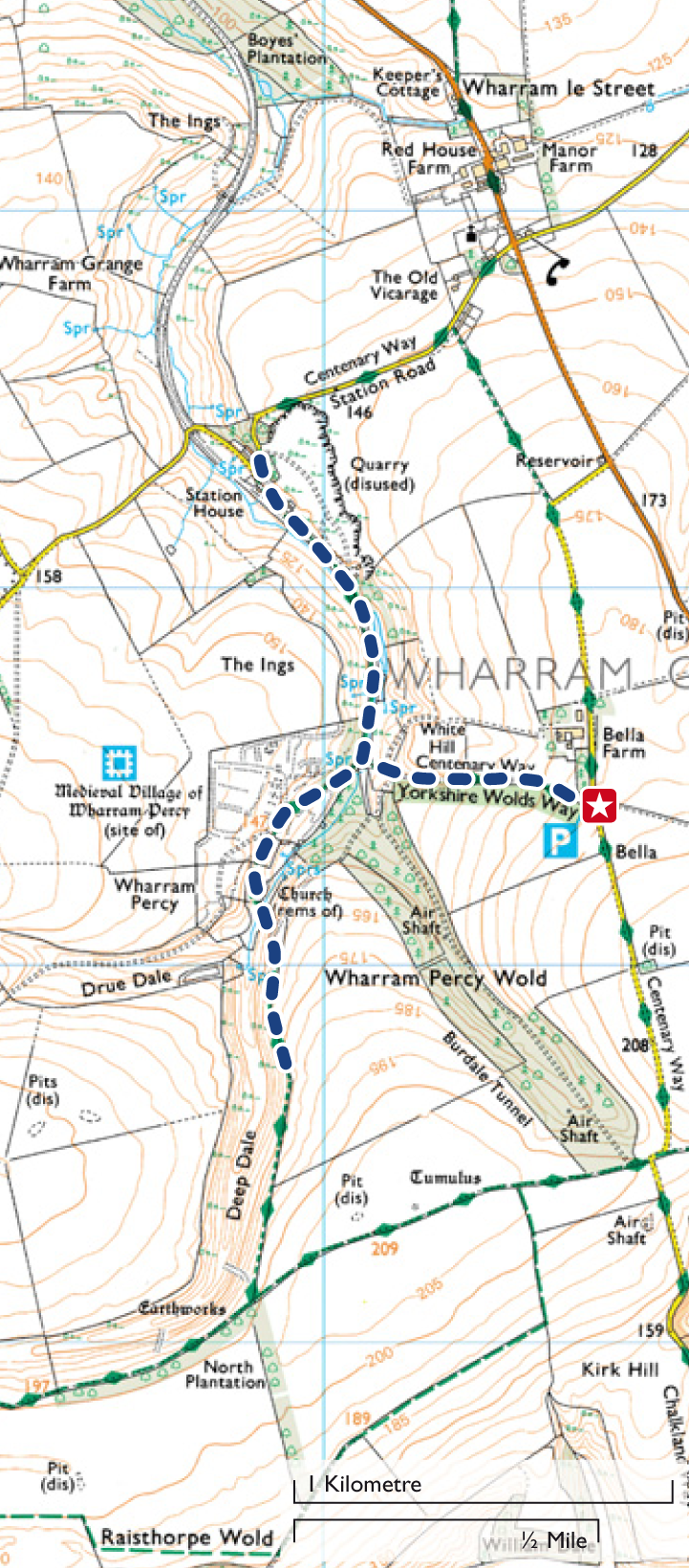

Locational Map

In human geography, the new approach became known as “locational” or “spatial analysis” or, to some, “spatial science.” It focused on spatial organization, and its key concepts were embedded into the functional region—the tributary area of a major node, whether a port, a market town, or a cityshopping centre. Movements of people, messages, goods, and so on, were organized through such nodal centres. These were structured hierarchically, producing systems of places—cities, towns, villages, etc.—whose spatial arrangement followed fundamental principles. One of the most influential models for these principles was developed by German geographer Walter Christaller in the early 1930s, though it attracted little attention for two decades.

This map shows the locational marginal price or LMP for each transmission zone in the region PJM serves. The legend in the bottom right corner of the map shows color coded values for LMP; these values are reflected on the map. You can zoom in on a specific location of the map for details. Creating beautifully designed custom maps with Mapme is simple, and doesn’t require any coding or GIS skills! All you need to do is: Create a Mapme account. Add or import locations. For each location, you can add descriptions, photos, videos, and more. Choose a map layout. Select the style that best suits your goals and audience. Area map of Cuyahoga Valley National Park. JPEG Download JPG Viewable Map File (523.1 kB) PDF Download 2019 screen-viewable file (17.0 MB) Adobe Illustrator Download 2019 Adobe Illustrator print production file (8.7 MB).

Christaller’s central-place theory modeled settlement patterns in rural areas—the number and size of different places, their spacing, and the services they provided—according to principles of least-cost location. The assumption was that individuals want to minimize the time and cost involved in journeys to shops and offices, and thus the needed facilities should be both as close to their homes as possible and clustered together so that they can make as many purchases as possible in the same place. Likewise, businesses will want to maximize turnover, with people spending as much as possible on goods and services and as little as possible on transport. An efficient distribution of service centres was in the interest of both suppliers and consumers. Christaller showed that this required a hexagonal distribution of centres across a uniform plane (i.e., one that had no topographical barriers), with the smaller centres (providing fewer services) nested within the market areas of the larger.

Other works by non-geographers provided similar stimuli. Economists such as Edgar Hoover, August Lösch (who produced a theory similar to Christaller’s), Tord Palander, and Alfred Weber suggested that manufacturing industries be located to minimize both input costs (including the costs of transporting raw materials to a plant) and distribution costs (getting the final goods to market). Least-cost location was the goal, which could be modeled as a form of spatial economics. Efficient spatial organization involved minimizing movement costs, which was represented by an adaptation of the physicists’ classical gravity model. The amount of movement between two places should be a function of their size and the distance between them; i.e., size generates interaction, whereas distance attenuates it.

These hypothesized patterns stimulated much searching for order in the distribution of economic activities and movements between places. Use of the intervening areas between the nodes and channels was also investigated within the same paradigm. A 19th-century German landowner-economist, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, had modeled the location of agricultural production, involving a zonal patterning of activities consistent with minimizing the costs of transporting outputs to markets with the highest-intensity activities closest to the nodes and channels. Economists adapted this to the organization of land uses within cities: these, and the associated land values, should be zonally organized, with housing density decreasing away from the centre and the major routes radiating from it.

Finally, there was the issue of change within such spatial systems, on which the work of Swedish geographer Torsten Hägerstrand was seminal. He added spatial components to sociological and economic models of the diffusion of information. According to Hägerstrand, the main centres of innovation tend to be the largest cities, from which new ideas and practices spread down the urban hierarchies and across the intervening nonurban spaces according to the least-cost principles of distance-decay models. Later studies validated his model, with the best examples provided by the spread of infectious and contagious diseases.

The models of patterns and flows were synthesized to describe urban systems at two main scales: systems of cities, in which places were depicted as nodes in the organizational template, and cities as systems, focusing on their internal organization. The goal was not just to describe those systems and their operations but also to model them (statistically and mathematically), thus producing general knowledge about the spatial organization of society rather than just specific knowledge about individual places. Location-allocation models suggested both optimum locations for facilities and efficient flows between them. A new discipline, regional science, was launched by economist Walter Isard to study such systems and promote the application of the knowledge acquired. It failed to gain separate status within universities, but many geographers still participate in its conferences and publish in its journals.

By the late 1960s these new practices were synthesized in influential innovative textbooks on both sides of the North Atlantic. Notable examples included Peter Haggett’s Locational Analysis in Human Geography (1965), Richard Chorley and Haggett’s Models in Geography (1967), Ron Abler, John Adams, and Peter Gould’s Spatial Organization (1971), and Richard L. Morrill’s The Spatial Organization of Society (1970). Each emphasized the theme earlier pronounced by Wreford Watson that “geography is a discipline in distance.”

The early models made relatively simple assumptions regarding human behaviour; the principle of least effort predominated, with monetary considerations preeminent, and it was assumed that decisions were based on complete information. These were later relaxed, and more-realistic models of spatial behaviour were based on observed decision making in which the acquisition and use of information in spatial contexts took centre stage. Distance was one constraint on behaviour; it was not absolute, however, but manipulable, as patterns of accessibility could be changed. And as the behavioral contexts were altered, the learning and decision-making processes within them also changed, and the spatial organization of society was continually restructured.

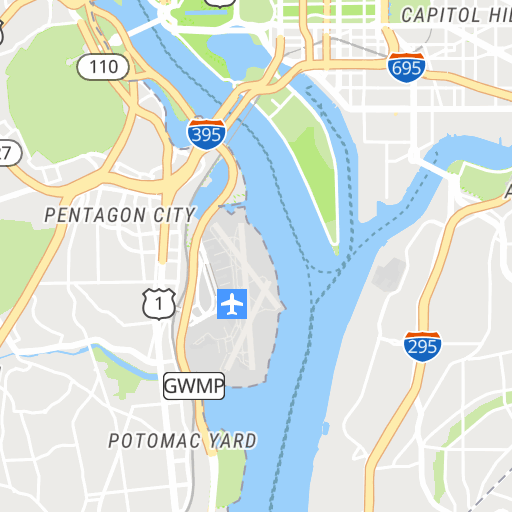

Map Locations By Address

Location Map Not Showing In Imessage

As research practices changed, so too did teaching. The earlier focus on field observation, map interpretation, and regional definition was replaced, and research methods for collecting and analyzing data—particularly statistical analysis—became compulsory elements in degree programs. New subdisciplines—notably urban geography—came rapidly to the fore, as systematic specialisms displaced regional courses from the core of many curricula. Other parts of the discipline—economic, social, political, and historical—were influenced by the theoretical and quantitative revolutions. What became known as a “new” human geography was created, initially at a few institutions in the United States and the United Kingdom but rapidly spread through the other Anglophone countries and later to a variety of other countries.